Building AES Encryption from Scratch in Rust

AES (Advanced Encryption Standard) is a widely used symmetric encryption algorithm. In this tutorial, we will implement AES encryption and decryption in Rust using a 128 bit key, and CBC (Cipher Block Chaining). By the end of this guide, you will have a solid understanding of AES and how to use it in Rust for secure data encryption. Link to the github project here: GitHub.

Disclaimer: you should not use the code written in this tutorial to encrypt anything important. It is still vulnerable to attacks this article was written for educational purposes only.

Prerequisites

Before we begin, make sure you have the following:

- Basic knowledge of Rust programming

- Rust installed on your system (installation guide)

Setting Up the Project

Create a new folder and use cargo init to initialise a new rust project. You can then use cargo run and you should see the “Hello World” message in your command line.

Encryption of a Single Block

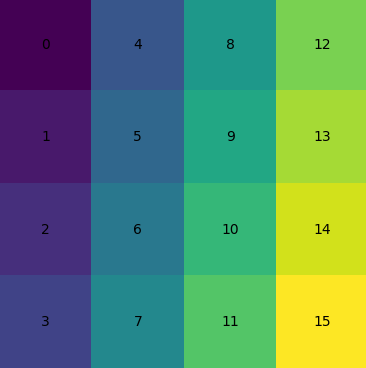

A plaintext block is a 4-by-4 matrix of bytes (represented in rust by an array of 16 8-bit integers [u8, 16]). It looks like this:

There are 4 transformations that we need to operate on the matrix.

- SubBytes(), swaps bytes using the S-Box substitution table.

- ShiftRows(), incrementally shifts the rows of the matrix

- MixColumns(), A matrix multiplication performed on each column

- AddRoundKey(), XOR the generated round key with the block

SubBytes()

The SubBytes function in AES is crucial for introducing non-linearity and confusion into the encryption process. It applies a non-linear transformation to each byte of the state matrix using a substitution box (S-Box). This helps thwart linear cryptanalysis attacks by making the relationship between the plaintext, ciphertext, and key complex.

We will start by populating the S-Box. This can be done by adding a constant in the main.rs file.

const SBOX: [u8; 256] = [

0x63, 0x7c, 0x77, 0x7b, 0xf2, 0x6b, 0x6f, 0xc5, 0x30, 0x01, 0x67, 0x2b, 0xfe, 0xd7, 0xab, 0x76,

0xca, 0x82, 0xc9, 0x7d, 0xfa, 0x59, 0x47, 0xf0, 0xad, 0xd4, 0xa2, 0xaf, 0x9c, 0xa4, 0x72, 0xc0,

0xb7, 0xfd, 0x93, 0x26, 0x36, 0x3f, 0xf7, 0xcc, 0x34, 0xa5, 0xe5, 0xf1, 0x71, 0xd8, 0x31, 0x15,

0x04, 0xc7, 0x23, 0xc3, 0x18, 0x96, 0x05, 0x9a, 0x07, 0x12, 0x80, 0xe2, 0xeb, 0x27, 0xb2, 0x75,

0x09, 0x83, 0x2c, 0x1a, 0x1b, 0x6e, 0x5a, 0xa0, 0x52, 0x3b, 0xd6, 0xb3, 0x29, 0xe3, 0x2f, 0x84,

0x53, 0xd1, 0x00, 0xed, 0x20, 0xfc, 0xb1, 0x5b, 0x6a, 0xcb, 0xbe, 0x39, 0x4a, 0x4c, 0x58, 0xcf,

0xd0, 0xef, 0xaa, 0xfb, 0x43, 0x4d, 0x33, 0x85, 0x45, 0xf9, 0x02, 0x7f, 0x50, 0x3c, 0x9f, 0xa8,

0x51, 0xa3, 0x40, 0x8f, 0x92, 0x9d, 0x38, 0xf5, 0xbc, 0xb6, 0xda, 0x21, 0x10, 0xff, 0xf3, 0xd2,

0xcd, 0x0c, 0x13, 0xec, 0x5f, 0x97, 0x44, 0x17, 0xc4, 0xa7, 0x7e, 0x3d, 0x64, 0x5d, 0x19, 0x73,

0x60, 0x81, 0x4f, 0xdc, 0x22, 0x2a, 0x90, 0x88, 0x46, 0xee, 0xb8, 0x14, 0xde, 0x5e, 0x0b, 0xdb,

0xe0, 0x32, 0x3a, 0x0a, 0x49, 0x06, 0x24, 0x5c, 0xc2, 0xd3, 0xac, 0x62, 0x91, 0x95, 0xe4, 0x79,

0xe7, 0xc8, 0x37, 0x6d, 0x8d, 0xd5, 0x4e, 0xa9, 0x6c, 0x56, 0xf4, 0xea, 0x65, 0x7a, 0xae, 0x08,

0xba, 0x78, 0x25, 0x2e, 0x1c, 0xa6, 0xb4, 0xc6, 0xe8, 0xdd, 0x74, 0x1f, 0x4b, 0xbd, 0x8b, 0x8a,

0x70, 0x3e, 0xb5, 0x66, 0x48, 0x03, 0xf6, 0x0e, 0x61, 0x35, 0x57, 0xb9, 0x86, 0xc1, 0x1d, 0x9e,

0xe1, 0xf8, 0x98, 0x11, 0x69, 0xd9, 0x8e, 0x94, 0x9b, 0x1e, 0x87, 0xe9, 0xce, 0x55, 0x28, 0xdf,

0x8c, 0xa1, 0x89, 0x0d, 0xbf, 0xe6, 0x42, 0x68, 0x41, 0x99, 0x2d, 0x0f, 0xb0, 0x54, 0xbb, 0x16

];

We will then write a function that takes a mutable reference to a block and replaces each item with its corresponding value in the S-Box.

fn sub_bytes(state: &mut [u8; 16]) {

for byte in state.iter_mut() {

*byte = SBOX[*byte as usize];

}

}

Now in we can update our main function to call sub_bytes with some test data.

fn main() {

let mut state: [u8; 16] = [

0x19, 0xa0, 0x9a, 0xe9,

0x3d, 0xf4, 0xc6, 0xf8,

0xe3, 0xe2, 0x8d, 0x48,

0xbe, 0x2b, 0x2a, 0x08,

];

let expected_sub_bytes: [u8; 16] = [

0xd4, 0xe0, 0xb8, 0x1e,

0x27, 0xbf, 0xb4, 0x41,

0x11, 0x98, 0x5d, 0x52,

0xae, 0xf1, 0xe5, 0x30,

];

sub_bytes(&mut state);

if state == expected_sub_bytes {

println!("It works!")

} else {

println!("Bytes substituted incorrectly")

}

}

And cargo run to make sure that it is working.

cargo run

Compiling aes-blog v0.1.0 (A:\Coding\chat app\aes-blog)

Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.30s

Running `target\debug\aes-blog.exe`

It works!

Now it works, we can move onto the next transformation

ShiftRows()

The ShiftRows function in AES provides diffusion, so that the influence of each byte is spread across multiple columns.

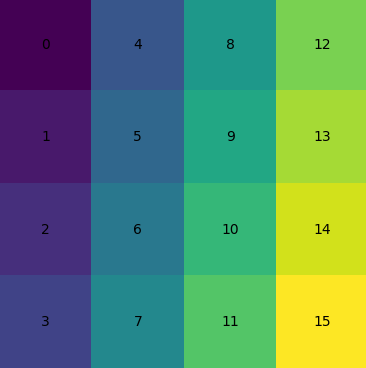

This transformation turns the matrix:

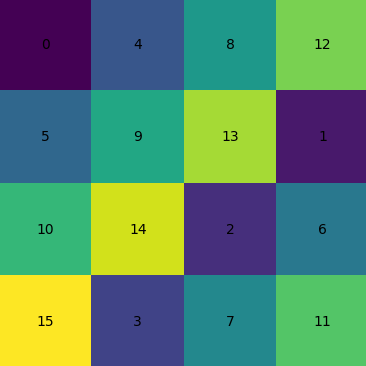

into the matrix:

by rotating the nth row n bits to the left (row 0 does not change).

fn shift_rows(state: &mut [u8; 16]) {

let mut temp = [0u8; 16];

temp.copy_from_slice(state);

// column 0

state[0] = temp[0];

state[1] = temp[5];

state[2] = temp[10];

state[3] = temp[15];

// column 1

state[4] = temp[4];

state[5] = temp[9];

state[6] = temp[14];

state[7] = temp[3];

// column 2

state[8] = temp[8];

state[9] = temp[13];

state[10] = temp[2];

state[11] = temp[7];

// column 3

state[12] = temp[12];

state[13] = temp[1];

state[14] = temp[6];

state[15] = temp[11];

}

Was the function I used. We can then write a similar test combining both functions in fn main

fn main() {

let mut state: [u8; 16] = [

0x19, 0xa0, 0x9a, 0xe9,

0x3d, 0xf4, 0xc6, 0xf8,

0xe3, 0xe2, 0x8d, 0x48,

0xbe, 0x2b, 0x2a, 0x08,

];

let expected_state: [u8; 16] = [

0xd4, 0xbf, 0x5d, 0x30,

0x27, 0x98, 0xe5, 0x1e,

0x11, 0xf1, 0xb8, 0x41,

0xae, 0xe0, 0xb4, 0x52,

];

sub_bytes(&mut state);

shift_rows(&mut state);

if state == expected_state {

println!("It works!")

} else {

println!("It doesn't work.")

}

}

The test passed so we can continue

MixColumns()

Operations performed on bytes in our matrix must have an inverse, and must be closed under the Galois field $GF(2^8)$. It follows that the addition (⊕) and multiplication (•) operations are somewhat different to those familiar to us.

Addition

a ⊕ b is just a simple bitwise XOR on a and b. For the purpose of our program this is the function that I have written.

fn add_blocks(state: &mut [u8; 16], b: &[u8]) {

for i in 0..16 {

state[i] ^= b[i];

}

}

This function won’t be limited for use with two [u8; 16] arrays so b can be an array of any size greater than 16 bytes. More on this will be explained in AddRoundKey().

Multiplication

Suppose we want to multiply two bytes, a and b, in $GF(2^8)$.

-

Polynomial Representation:

- $a = 0x57 = x^6 + x^4 + x^2 + x + 1$

- $b = 0x83 = x^7 + x + 1$

-

Polynomial Multiplication:

- $a \cdot b = (x^6 + x^4 + x^2 + x + 1) \cdot (x^7 + x + 1)$

- Expand this using the distributive property and simplify using XOR for addition.

-

Modulo Reduction:

- Reduce the polynomial result modulo $x^8 + x^4 + x^3 + x + 1$.

-

Result:

- $a \cdot b = (x^7 + x^6 + 1) = 0xC1$

In rust Galois multiplication looks like this

fn gal_mul (a: u8, b: u8) -> u8 {

let mut result: u8 = 0; // Result of the multiplication

let mut a = a; // Copy of the first operand

let mut b = b; // Copy of the second operand

// Irreducible polynomial for GF(2^8)

const IRREDUCIBLE_POLY: u8 = 0x1b; // (x^8) + x^4 + x^3 + x + 1

// Process each bit of the second operand

while b != 0 {

// If the least significant bit of b is 1, add the current a to the result

if (b & 1) != 0 {

result ^= a; // XOR is used instead of addition in GF(2^8)

}

// Shift a to the left, which corresponds to multiplying by x in GF(2^8)

let high_bit_set = (a & 0x80) != 0; // Check if the high bit (x^7) is set

a <<= 1; // Multiply a by x

// If the high bit was set before shifting, reduce a modulo the irreducible polynomial

if high_bit_set {

a ^= IRREDUCIBLE_POLY; // Perform the reduction

}

// Shift b to the right, moving to the next bit

b >>= 1;

}

result

}

Transformation

Finally, for each column $c$, MixColumns() performs the following matrix multiplication:

in rust:

fn mix_columns(state: &mut [u8; 16]) {

let temp = *state;

// column 0

state[0] = gal_mul(temp[0], 0x02) ^ gal_mul(temp[1], 0x03) ^ temp[2] ^ temp[3];

state[1] = temp[0] ^ gal_mul(temp[1], 0x02) ^ gal_mul(temp[2], 0x03) ^ temp[3];

state[2] = temp[0] ^ temp[1] ^ gal_mul(temp[2], 0x02) ^ gal_mul(temp[3], 0x03);

state[3] = gal_mul(temp[0], 0x03) ^ temp[1] ^ temp[2] ^ gal_mul(temp[3], 0x02);

// column 1

state[4] = gal_mul(temp[4], 0x02) ^ gal_mul(temp[5], 0x03) ^ temp[6] ^ temp[7];

state[5] = temp[4] ^ gal_mul(temp[5], 0x02) ^ gal_mul(temp[6], 0x03) ^ temp[7];

state[6] = temp[4] ^ temp[5] ^ gal_mul(temp[6], 0x02) ^ gal_mul(temp[7], 0x03);

state[7] = gal_mul(temp[4], 0x03) ^ temp[5] ^ temp[6] ^ gal_mul(temp[7], 0x02);

// column 2

state[8] = gal_mul(temp[8], 0x02) ^ gal_mul(temp[9], 0x03) ^ temp[10] ^ temp[11];

state[9] = temp[8] ^ gal_mul(temp[9], 0x02) ^ gal_mul(temp[10], 0x03) ^ temp[11];

state[10] = temp[8] ^ temp[9] ^ gal_mul(temp[10], 0x02) ^ gal_mul(temp[11], 0x03);

state[11] = gal_mul(temp[8], 0x03) ^ temp[9] ^ temp[10] ^ gal_mul(temp[11], 0x02);

// column 3

state[12] = gal_mul(temp[12], 0x02) ^ gal_mul(temp[13], 0x03) ^ temp[14] ^ temp[15];

state[13] = temp[12] ^ gal_mul(temp[13], 0x02) ^ gal_mul(temp[14], 0x03) ^ temp[15];

state[14] = temp[12] ^ temp[13] ^ gal_mul(temp[14], 0x02) ^ gal_mul(temp[15], 0x03);

state[15] = gal_mul(temp[12], 0x03) ^ temp[13] ^ temp[14] ^ gal_mul(temp[15], 0x02);

}

Now in main.rs we can test this function.

fn main() {

let mut state: [u8; 16] = [

0x19, 0xa0, 0x9a, 0xe9,

0x3d, 0xf4, 0xc6, 0xf8,

0xe3, 0xe2, 0x8d, 0x48,

0xbe, 0x2b, 0x2a, 0x08,

];

let expected_state: [u8; 16] = [

0xba, 0x1e, 0xb6, 0xd8,

0x43, 0x67, 0x4d, 0x9e,

0x25, 0xf8, 0xd8, 0xc1,

0x38, 0x9e, 0xd9, 0xc8,

];

mix_columns(&mut state);

if state == expected_state {

println!("Mix columns works!")

}

}

AddRoundKey()

AES encryption involves doing multiple rounds of the four transformations. For a 128 bit key we do 10 rounds. The AddRoundKey() function in AES is a crucial step in each round of the encryption and decryption process. It combines the state matrix with a subkey derived from the main encryption key.

First we must write a function to generate the round key for our 128 bit key.

Example of Key Expansion for AES-128

-

Original Key:

- Suppose the original key is $ k = [k_0, k_1, k_2, k_3] $, where each $ k_i $ is a 4-byte word.

-

Initial Round Key:

- The initial round key is simply the original key.

-

Generate Subsequent Round Keys:

- For each subsequent word $ w_i $ in the expanded key:

- If $ i $ is a multiple of 4, perform the following:

- Rotate the previous word $ w_{i-1} $.

- Apply the S-box to each byte of the rotated word.

- XOR the result with the round constant $ Rcon[i/4] $.

- XOR this result with $ w_{i-4} $ to get $ w_i $.

- Otherwise, simply XOR the previous word $ w_{i-1} $ with $ w_{i-4} $ to get $ w_i $.

- If $ i $ is a multiple of 4, perform the following:

- For each subsequent word $ w_i $ in the expanded key:

Rust

const R_CONSTANTS: [u8;11] = [0x00, 0x01, 0x02, 0x04, 0x08, 0x10, 0x20, 0x40, 0x80, 0x1B, 0x36];

// Expands the key into multiple round keys.

// Nk = 4 as key = 128

// 10 passes * 16 bytes + 16 bytes = 176

fn key_expansion(key: &[u8; 16], expanded_key: &mut [u8; 176]) {

// first 16 bits are the original key

expanded_key[0..16].copy_from_slice(key);

let mut i = 16;

let mut temp = [0u8; 4];

while i < 176 {

temp.copy_from_slice(&expanded_key[i-4..i]);

if i % 16 == 0 {

// Rotate left

temp.rotate_left(1);

// Substitute bytes using S-box

for j in 0..4 {

temp[j] = SBOX[temp[j] as usize];

}

// XOR with round constant

temp[0] ^= R_CONSTANTS[i / 16];

}

for j in 0..4 {

expanded_key[i] = expanded_key[i - 16] ^ temp[j];

i += 1;

}

}

}

Now that we’ve generated the round key we have what we need to encrypt a block.

Encrypt a block

To perform AES encryption, the main functions—such as SubBytes(), ShiftRows(), MixColumns(), and AddRoundKey()—must be combined sequentially according to the AES algorithm’s structure. The process starts by applying the AddRoundKey() function with the initial key. Then, for each round (10 rounds for AES-128), the state undergoes SubBytes(), ShiftRows(), MixColumns(), and AddRoundKey(). In the final round, MixColumns() is omitted, and the final AddRoundKey() completes the encryption. By chaining these functions together, you transform the plaintext into ciphertext securely.

// Encrypts a single block of 16 bytes using AES-128.

fn aes_encrypt_block(input: &[u8; 16], output: &mut [u8; 16], key: &[u8; 16]) {

let mut state = *input;

let mut expanded_key = [0u8; 176];

key_expansion(key, &mut expanded_key);

add_blocks(&mut state, &expanded_key[0..16]);

for round in 1..10 {

sub_bytes(&mut state);

shift_rows(&mut state);

mix_columns(&mut state);

// Add round key

add_blocks(&mut state, &expanded_key[round * 16..(round + 1) * 16]);

}

sub_bytes(&mut state);

shift_rows(&mut state);

add_blocks(&mut state, &expanded_key[160..176]);

output.copy_from_slice(&state);

}

Let’s do a test to make sure that this is working as it should.

fn main() {

let state: [u8; 16] = [

0x00, 0x11, 0x22, 0x33,

0x44, 0x55, 0x66, 0x77,

0x88, 0x99, 0xaa, 0xbb,

0xcc, 0xdd, 0xee, 0xff,

];

let expected_state: [u8; 16] = [

0x69, 0xc4, 0xe0, 0xd8,

0x6a, 0x7b, 0x04, 0x30,

0xd8, 0xcd, 0xb7, 0x80,

0x70, 0xb4, 0xc5, 0x5a,

];

let key: [u8; 16] = [

0x00, 0x01, 0x02, 0x03,

0x04, 0x05, 0x06, 0x07,

0x08, 0x09, 0x0a, 0x0b,

0x0c, 0x0d, 0x0e, 0x0f,

];

let mut output: [u8; 16] = [0u8; 16];

aes_encrypt_block(&state, &mut output, &key);

if output == expected_state {

println!("Full block AES-128 encryption works!")

}

}

Decryption of a Single Block

Decryption of a block is just a case of inverting each of the steps we took. Writing inverse functions to each transformation is fairly straightforward. Here is the code that used:

const INV_SBOX: [u8; 256] = [

0x52, 0x09, 0x6a, 0xd5, 0x30, 0x36, 0xa5, 0x38, 0xbf, 0x40, 0xa3, 0x9e, 0x81, 0xf3, 0xd7, 0xfb,

0x7c, 0xe3, 0x39, 0x82, 0x9b, 0x2f, 0xff, 0x87, 0x34, 0x8e, 0x43, 0x44, 0xc4, 0xde, 0xe9, 0xcb,

0x54, 0x7b, 0x94, 0x32, 0xa6, 0xc2, 0x23, 0x3d, 0xee, 0x4c, 0x95, 0x0b, 0x42, 0xfa, 0xc3, 0x4e,

0x08, 0x2e, 0xa1, 0x66, 0x28, 0xd9, 0x24, 0xb2, 0x76, 0x5b, 0xa2, 0x49, 0x6d, 0x8b, 0xd1, 0x25,

0x72, 0xf8, 0xf6, 0x64, 0x86, 0x68, 0x98, 0x16, 0xd4, 0xa4, 0x5c, 0xcc, 0x5d, 0x65, 0xb6, 0x92,

0x6c, 0x70, 0x48, 0x50, 0xfd, 0xed, 0xb9, 0xda, 0x5e, 0x15, 0x46, 0x57, 0xa7, 0x8d, 0x9d, 0x84,

0x90, 0xd8, 0xab, 0x00, 0x8c, 0xbc, 0xd3, 0x0a, 0xf7, 0xe4, 0x58, 0x05, 0xb8, 0xb3, 0x45, 0x06,

0xd0, 0x2c, 0x1e, 0x8f, 0xca, 0x3f, 0x0f, 0x02, 0xc1, 0xaf, 0xbd, 0x03, 0x01, 0x13, 0x8a, 0x6b,

0x3a, 0x91, 0x11, 0x41, 0x4f, 0x67, 0xdc, 0xea, 0x97, 0xf2, 0xcf, 0xce, 0xf0, 0xb4, 0xe6, 0x73,

0x96, 0xac, 0x74, 0x22, 0xe7, 0xad, 0x35, 0x85, 0xe2, 0xf9, 0x37, 0xe8, 0x1c, 0x75, 0xdf, 0x6e,

0x47, 0xf1, 0x1a, 0x71, 0x1d, 0x29, 0xc5, 0x89, 0x6f, 0xb7, 0x62, 0x0e, 0xaa, 0x18, 0xbe, 0x1b,

0xfc, 0x56, 0x3e, 0x4b, 0xc6, 0xd2, 0x79, 0x20, 0x9a, 0xdb, 0xc0, 0xfe, 0x78, 0xcd, 0x5a, 0xf4,

0x1f, 0xdd, 0xa8, 0x33, 0x88, 0x07, 0xc7, 0x31, 0xb1, 0x12, 0x10, 0x59, 0x27, 0x80, 0xec, 0x5f,

0x60, 0x51, 0x7f, 0xa9, 0x19, 0xb5, 0x4a, 0x0d, 0x2d, 0xe5, 0x7a, 0x9f, 0x93, 0xc9, 0x9c, 0xef,

0xa0, 0xe0, 0x3b, 0x4d, 0xae, 0x2a, 0xf5, 0xb0, 0xc8, 0xeb, 0xbb, 0x3c, 0x83, 0x53, 0x99, 0x61,

0x17, 0x2b, 0x04, 0x7e, 0xba, 0x77, 0xd6, 0x26, 0xe1, 0x69, 0x14, 0x63, 0x55, 0x21, 0x0c, 0x7d

];

fn inv_sub_bytes(state: &mut [u8; 16]) {

for byte in state.iter_mut() {

*byte = INV_SBOX[*byte as usize];

}

}

fn inv_shift_rows(state: &mut [u8; 16]) {

let mut temp = [0u8; 16];

temp.copy_from_slice(state);

state[0] = temp[0];

state[4] = temp[4];

state[8] = temp[8];

state[12] = temp[12];

state[1] = temp[13];

state[2] = temp[10];

state[3] = temp[7];

state[5] = temp[1];

state[6] = temp[14];

state[7] = temp[11];

state[9] = temp[5];

state[10] = temp[2];

state[11] = temp[15];

state[13] = temp[9];

state[14] = temp[6];

state[15] = temp[3];

}

fn inv_mix_columns(state: &mut [u8; 16]) {

let temp = *state;

state[0] = gal_mul(temp[0], 0x0e) ^ gal_mul(temp[1], 0x0b) ^ gal_mul(temp[2], 0x0d) ^ gal_mul(temp[3], 0x09);

state[1] = gal_mul(temp[0], 0x09) ^ gal_mul(temp[1], 0x0e) ^ gal_mul(temp[2], 0x0b) ^ gal_mul(temp[3], 0x0d);

state[2] = gal_mul(temp[0], 0x0d) ^ gal_mul(temp[1], 0x09) ^ gal_mul(temp[2], 0x0e) ^ gal_mul(temp[3], 0x0b);

state[3] = gal_mul(temp[0], 0x0b) ^ gal_mul(temp[1], 0x0d) ^ gal_mul(temp[2], 0x09) ^ gal_mul(temp[3], 0x0e);

state[4] = gal_mul(temp[4], 0x0e) ^ gal_mul(temp[5], 0x0b) ^ gal_mul(temp[6], 0x0d) ^ gal_mul(temp[7], 0x09);

state[5] = gal_mul(temp[4], 0x09) ^ gal_mul(temp[5], 0x0e) ^ gal_mul(temp[6], 0x0b) ^ gal_mul(temp[7], 0x0d);

state[6] = gal_mul(temp[4], 0x0d) ^ gal_mul(temp[5], 0x09) ^ gal_mul(temp[6], 0x0e) ^ gal_mul(temp[7], 0x0b);

state[7] = gal_mul(temp[4], 0x0b) ^ gal_mul(temp[5], 0x0d) ^ gal_mul(temp[6], 0x09) ^ gal_mul(temp[7], 0x0e);

state[8] = gal_mul(temp[8], 0x0e) ^ gal_mul(temp[9], 0x0b) ^ gal_mul(temp[10], 0x0d) ^ gal_mul(temp[11], 0x09);

state[9] = gal_mul(temp[8], 0x09) ^ gal_mul(temp[9], 0x0e) ^ gal_mul(temp[10], 0x0b) ^ gal_mul(temp[11], 0x0d);

state[10] = gal_mul(temp[8], 0x0d) ^ gal_mul(temp[9], 0x09) ^ gal_mul(temp[10], 0x0e) ^ gal_mul(temp[11], 0x0b);

state[11] = gal_mul(temp[8], 0x0b) ^ gal_mul(temp[9], 0x0d) ^ gal_mul(temp[10], 0x09) ^ gal_mul(temp[11], 0x0e);

state[12] = gal_mul(temp[12], 0x0e) ^ gal_mul(temp[13], 0x0b) ^ gal_mul(temp[14], 0x0d) ^ gal_mul(temp[15], 0x09);

state[13] = gal_mul(temp[12], 0x09) ^ gal_mul(temp[13], 0x0e) ^ gal_mul(temp[14], 0x0b) ^ gal_mul(temp[15], 0x0d);

state[14] = gal_mul(temp[12], 0x0d) ^ gal_mul(temp[13], 0x09) ^ gal_mul(temp[14], 0x0e) ^ gal_mul(temp[15], 0x0b);

state[15] = gal_mul(temp[12], 0x0b) ^ gal_mul(temp[13], 0x0d) ^ gal_mul(temp[14], 0x09) ^ gal_mul(temp[15], 0x0e);

}

fn aes_decrypt_block(input: &[u8; 16], output: &mut [u8; 16], key: &[u8; 16]) {

let mut state = *input;

let mut expanded_key = [0u8; 176];

key_expansion(key, &mut expanded_key);

add_blocks(&mut state, &expanded_key[160..176]);

for round in (1..10).rev() {

inv_shift_rows(&mut state);

inv_sub_bytes(&mut state);

add_blocks(&mut state, &expanded_key[round * 16..(round + 1) * 16]);

inv_mix_columns(&mut state);

}

inv_shift_rows(&mut state);

inv_sub_bytes(&mut state);

add_blocks(&mut state, &expanded_key[0..16]);

output.copy_from_slice(&state);

}

You may want to seperate functions from the main file for your convenience.

Encryption of Many Blocks

The simplest way to encrypt blocks is to process 16 bytes at a time. However, repeated sequences create patterns, reducing security. Cipher Block Chaining (CBC) prevents this by XORing each plaintext block with the previous ciphertext block before encryption. This ensures identical plaintext blocks produce different ciphertext blocks. An Initialization Vector (IV) is used for the first block to add randomness, further enhancing security.

CBC is demonstrated for simplicity. It is vulnerable to many attacks and more in depth information about this can be found here.

Example

Suppose we want to encrypt a series of plaintext blocks $ P_1, P_2, \ldots, P_n $:

- Choose a unique IV.

- Encrypt the first block: $ C_1 = E_K(P_1 \oplus IV) $

- Encrypt subsequent blocks: $ C_i = E_K(P_i \oplus C_{i-1}) $ for $ i > 1 $

For decryption:

- Decrypt the first block: $ P_1 = D_K(C_1) \oplus IV $

- Decrypt subsequent blocks: $ P_i = D_K(C_i) \oplus C_{i-1} $ for $ i > 1 $

Rust:

pub fn aes_encrypt_vector (plaintext: &Vec<u8>, iv: &[u8; 16], key: &[u8; 16],) -> Result<Vec<u8>, &'static str> {

if plaintext.len() % 16 != 0 {

return Err("The plaintext isn't a multiple of 16 bits");

}

let mut ciphertext: Vec<u8> = Vec::new();

let mut last_block = *iv;

let num_blocks = plaintext.len() / 16;

for block_index in 0..num_blocks {

let mut block: [u8; 16] = [0; 16];

for a in 0..16 {

block[a] = plaintext[(16 * block_index) + a]

}

// xor blocks together

add_blocks(&mut block, &last_block);

// encrypt block

aes_encrypt_block(&block.clone(), &mut block, &key);

// last_block = encrypted block

last_block = block;

for b in block {

ciphertext.push(b);

}

}

Ok(ciphertext)

}

pub fn aes_decrypt_vector (ciphertext: &Vec<u8>, iv: &[u8; 16], key: &[u8; 16]) -> Result<Vec<u8>, &'static str> {

if ciphertext.len() % 16 != 0 {

return Err("The plaintext isn't a multiple of 16 bits");

}

let num_blocks = ciphertext.len() / 16;

let mut last = iv.clone();

let mut plaintext = vec![];

for block_index in 0..num_blocks {

let mut block: [u8; 16] = [0; 16];

for a in 0..16 {

block[a] = ciphertext[(16 * block_index) + a]

}

let xor = last;

last = block;

// decrypt block

aes_decrypt_block(&block.clone(), &mut block, &key);

// xor blocks together

add_blocks(&mut block, &xor);

for b in block {

plaintext.push(b);

}

}

Ok(plaintext)

}

Now let’s one last test:

fn main() {

let key: [u8; 16] = [

0x2b, 0x7e, 0x15, 0x16,

0x28, 0xae, 0xd2, 0xa6,

0xab, 0xf7, 0x15, 0x88,

0x09, 0xcf, 0x4f, 0x3c,

];

let iv: [u8; 16] = [

0x00, 0x01, 0x02, 0x03,

0x04, 0x05, 0x06, 0x07,

0x08, 0x09, 0x0A, 0x0B,

0x0C, 0x0D, 0x0E, 0x0F,

];

let plain: Vec<u8> = vec![

0x6b, 0xc1, 0xbe, 0xe2,

0x2e, 0x40, 0x9f, 0x96,

0xe9, 0x3d, 0x7e, 0x11,

0x73, 0x93, 0x17, 0x2a,

0x6b, 0xc1, 0xbe, 0xe2,

0x2e, 0x40, 0x9f, 0x96,

0xe9, 0x3d, 0x7e, 0x11,

0x73, 0x93, 0x17, 0x2a,

0x6b, 0xc1, 0xbe, 0xe2,

0x2e, 0x40, 0x9f, 0x96,

0xe9, 0x3d, 0x7e, 0x11,

0x73, 0x93, 0x17, 0x2a,

0x6b, 0xc1, 0xbe, 0xe2,

0x2e, 0x40, 0x9f, 0x96,

0xe9, 0x3d, 0x7e, 0x11,

0x73, 0x93, 0x17, 0x2a,

0x6b, 0xc1, 0xbe, 0xe2,

0x2e, 0x40, 0x9f, 0x96,

0xe9, 0x3d, 0x7e, 0x11,

0x73, 0x93, 0x17, 0x2a,

];

let cipher: Vec<u8> = vec![

0x76, 0x49, 0xab, 0xac,

0x81, 0x19, 0xb2, 0x46,

0xce, 0xe9, 0x8e, 0x9b,

0x12, 0xe9, 0x19, 0x7d,

0x4c, 0xbb, 0xc8, 0x58,

0x75, 0x6b, 0x35, 0x81,

0x25, 0x52, 0x9e, 0x96,

0x98, 0xa3, 0x8f, 0x44,

0x9f, 0x6f, 0x07, 0x96,

0xee, 0x3e, 0x47, 0xb0,

0xd8, 0x7c, 0x76, 0x1b,

0x20, 0x52, 0x7f, 0x78,

0x07, 0x01, 0x34, 0x08,

0x5f, 0x02, 0x75, 0x17,

0x55, 0xef, 0xca, 0x3b,

0x4c, 0xdc, 0x7d, 0x62,

0x1d, 0x93, 0x10, 0xca,

0xac, 0x69, 0xe1, 0xff,

0xee, 0xe0, 0x71, 0x20,

0x25, 0x02, 0xfa, 0x70,

];

let c = aes_encrypt_vector(&plain, &iv, &key).unwrap();

if c == cipher {

println!("Encrypted matches ciphertext")

}

if plain == aes_decrypt_vector(&c, &iv, &key).unwrap() {

println!("Plaintext and decrypted match.")

}

}

Now we’ve got secure symmetric encryption using AES-128 with CBC.

References

FIPS 197, Advanced Encryption Standard (AES)

Daemen, J., & Rijmen, V. (2002). The Design of Rijndael: AES